‘The Ability to Give and Receive Love’: Researchers Look at Effects of Acceptance, Rejection

Even at 90 years old, Ronald P. Rohner still works 365 days a year.

That’s holidays, weekends, sick days, and everything in between, he says. But the professor emeritus and director of the Center for the Study of Interpersonal Acceptance and Rejection knows he’s not going to be able to keep pace forever – no matter how much he wants.

He’s picked Sumbleen Ali ’21 Ph.D., a research scientist at the Center and an assistant professor at SUNY Oneonta, to carry on the Center’s global mission, as they seek to advance research on Interpersonal Acceptance-Rejection Theory, known as IPARTheory, and continue to expand its reach worldwide.

It’s part of what the two have put into their latest book, “Global Perspectives on Parental Acceptance and Rejection: Lessons Learned from IPARTheory,” published this spring.

Rohner and Ali sat with UConn Today recently to talk about interpersonal acceptance and rejection, what started Rohner’s study of it, and what their advice is for lay people.

How did you get started with this research?

Rohner: It all came from a passage in this 1956 book that was my favorite textbook when I was an undergraduate. The author said that, in general, rejected children tend to be fearful, insecure, attention seeking, jealous, hostile, and lonely. Because of some previous experiences I’d had working in Morocco, I thought that wouldn’t be true. That may be true for Americans, but that's not true for people all over the world – especially the people I’d encountered in Morocco in the 1950s. One of my first assignments in graduate school was to use the cross-cultural survey method, that’s when you draw a sample of societies from around the world and code them in a certain way to see what’s true and not true for people worldwide. When I did the analysis, I discovered that some of what was said in my undergraduate book was true and some of it wasn’t. That completely captured my attention. Every class thereafter during my graduate career if I could possibly fit it in, I built on that initial cross-cultural study, and when I came to UConn in 1964, I continued doing these kinds of cross-cultural studies to find out what we're really like as human beings.

What are some of the things you’ve found?

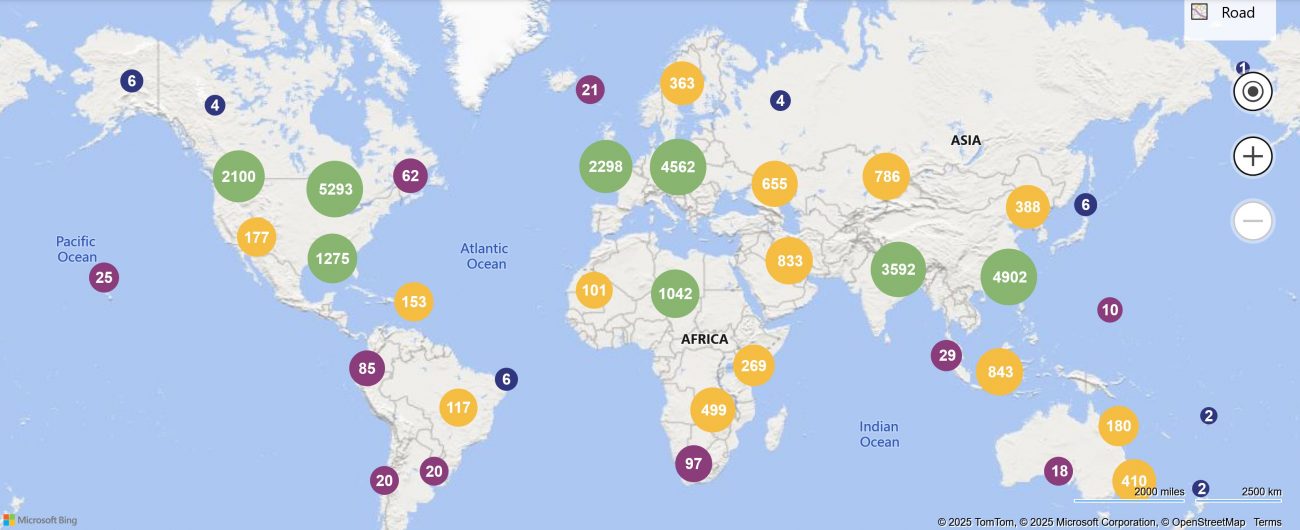

Rohner: We’ve worked with several hundred thousand people over the past 60-some-odd years on every continent except Antarctica, and while doing that, we’ve learned many lessons about what we're like and not like as human beings. The beauty of the work we do is that we can now empirically document three things, among others. First, humans everywhere – in any place in the world that we’ve found so far - understand themselves to be cared about or not cared about in the same four ways. So far, no exceptions. Second, if you feel the person or people who are most important to you – these are usually parents when we're kids and intimate partners when we're adults, but there could be others like teachers or coaches – if you feel that person doesn't really want you, appreciate you, care about you, love you, if you feel rejected by that person, most people will respond in exactly the same way. A cluster of 10 things start to happen. We get anxious, insecure. We have anger problems. Our self-esteem is impaired. Children can have issues of cognitive distortions, in which they start to think about themselves in distorted ways. The third important lesson comes from Sumbleen’s work.

Ali: I came to UConn as a psychology student and enjoyed working with Ron so much that I decided to pursue a graduate degree in human development and family sciences. In conversations about IPARTheory, we developed an argument that parental acceptance and rejection might be rooted in our shared biocultural evolution, and I wanted to investigate how that shows up in the brain. This became the focus of my dissertation - the first in affective neuroscience at UConn - under the guidance of my Ph.D. advisors, Preston Britner and Ron Rohner. The research examined how early parental experiences shape emotional regulation. We scanned the brains of students who reported either parental acceptance or rejection while they played a simulated ball-tossing game designed to mimic social exclusion. Those with rejection histories showed more activity in areas linked to emotion and memory, suggesting they were re-experiencing past rejection. Participants who felt loved showed more activation in regions tied to rational thinking, possibly reframing the experience. Now, we’re analyzing resting-state brain data to see whether differences in brain connectivity appear even without an external task.

Why is this research so important?

Rohner: If you bang your thumb, it's going to hurt. Two weeks from now you're going to remember that when you did that, it hurt - but you’re probably not going to feel the pain. With rejection, though, every time you think about it for the rest of your life, it can light up your brain in the same way it did when it was happening. I sometimes say the childhood of rejected kids can bully them for the rest of their lives. A rejected child who as an adult gets into an intimate relationship with a partner who is patient and has other supportive traits can help the rejected person to start feeling cared about, maybe for the first time in her or his life. That can go a long way, but we haven't found anything yet that completely erases those experiences of early childhood.

Really, there aren’t any exceptions?

Ali: IPARTheory does identify a group of people we call ‘affective copers.’ These are individuals who might have experienced rejection from their parents or one parent, but they don't show psychological maladjustment to the same degree that other rejected individuals do because they had a buffer in their life, like a grandparent, an intimate partner, a friend, or a sibling who provided them with love and shelter and protection.

Rohner: We're exploring this theory of ‘affective copers’ because if we can find out what helps some people then maybe clinicians and other professionals can use that information with their clients to help them overcome their feelings of rejection. We have clinical partners all over the world - in the courts, schools, clinical settings. IPARTheory is being applied everywhere to help people with custody issues, parental alienation, etcetera. The reason this has become so widespread around the world is because it works for people everywhere.

People experience rejection all the time. How do how do some get through these situations better than others?

Rohner: Someone like a bus driver, for instance, you don't really care about them, so if they’re snotty to you, you're going to get irritated, but it will roll off easier. If you're ostracized from a peer group, that hurts too, and it’ll light up the brain but it's not going to have the same long-term effects as being hurt by an attachment figure. We have an adage in IPARTheory that we call the ‘emotional moon phenomenon’ that says: ‘Sometimes I'm happy, sometimes I'm blue. My mood all day depends on my relationship with you.’ An attachment figure for us in IPARTheory is someone with whom your feelings of happiness and welfare are to some extent dependent on your relationship with that other person. When things are going well between you and them, times are great. When things start going out of whack, you get upset and stay that way. That's an attachment figure. The bus driver is not an attachment figure. The breakup of even a bad intimate relationship is painful and will have an enduring effect for many people for a long time, but if you come from a loving family when that relationship ends there will be a period of upset, but you’ll tap the resilience from your prior background to get you through the hard times.

Do you have any advice for lay people?

Rohner: There’s no single experience in human life that's more important, that has greater impact over the entire course of your life than the experience of being cared about by the people who are most important to you. That's the fundamental lesson behind all of this. I don't care what somebody says about what's going on in a relationship, it’s what you feel is going on that makes the difference in your life.

Ali: Early experiences of parental love, acceptance, or rejection leave children with far more than just memories. They fundamentally shape how children, and the adults they become, perceive themselves, relate to others, and make sense of the world. To that end, we have to keep working to understand why some parents love their children versus why others don't, the ability to give and receive love. Our goal is for people to better understand themselves and understand those around them. Through our research and advocacy, we want to build a better community and foster healthy interpersonal relationships by improving our understanding of one another.

Latest UConn Today

- Neag School of Education Hosts “Why Teach, Why Now” Contest for Early College Experience StudentsHigh school students submitted short essays or videos explaining why they want to become urban educators

- UConn Students Combat Opioid Crisis in CT through Adopt a Health District ProgramThrough the program, UConn students help Connecticut communities tackle the opioid crisis, from Narcan training to safe medication disposal techniques

- UConn Entrepreneur Aims to Revolutionize Men’s Health CareReza Amin’s Bastion Health creates virtual, confidential, progressive approach to medical screening to help save lives

- UConn’s Sir Cato T. Laurencin Recognized as Springer Nature Editor of DistinctionSir Cato T. Laurencin, MD, Ph.D., K.C.S.L, has received a 2025 Springer Nature Editor of Distinction Award. The award is given to exceptional editors who have demonstrated commitment to upholding scientific accuracy and advancing discovery.

- UConn Health Minute: Two Lives, One TeamAn expectant mom learned she suffered a life-threatening condition. But the high risk pregnancy team at UConn Health had the expertise to keep mom safe as she delivered a healthy baby.

- Overcoming Engineering Challenges Was No Problem for This Student TeamA joint mechanical and electrical and computer engineering Senior Design team tackled various problems in the midst of an electric boat competition