50 Years in the Lab

Many clinical lab tests that used to take a week or longer to yield results now take less than an hour, thanks to decades of advancement in laboratory medicine.

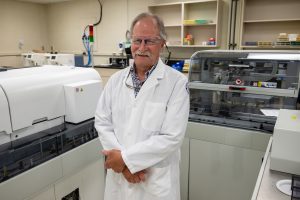

UConn Health Professor Emeritus of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Sidney Hopfer ’75 MS, ’79 Ph.D. would know. He goes back to when it was a relatively new discipline.

Then a 21-year-old aspiring veterinarian fresh out of Colorado State University with a biology degree, Hopfer was drafted into the Army before he could start veterinary school and served in Vietnam as a combat infantry platoon leader and company commander.

By the time 1st Lt. Hopfer was discharged in 1971, the fall semester already had begun. He started a master’s degree program in pathobiology at UConn the following January.

“I was accepted in the Department of Veterinary Pathology at Storrs, where they train veterinarians to become pathologists,” Hopfer says. “I received a master’s degree, at the time when laboratory testing was becoming a discipline.”

In 1975, as a Ph.D. student, Hopfer started working as a graduate assistant with Dr. F. William Sunderman, who was chair of the Department of Laboratory Medicine of what was then known as the UConn Health Center.

“That was the beginning of my sojourn at UConn Health,” Hopfer says. “I performed research with Bill on trace metals, nickel mostly, for years. When I completed requirements for a Ph.D., I was accepted into the residency program in the clinical laboratory. Part of a resident’s responsibility in laboratory medicine/pathology was to develop new laboratory tests to address evolving changes in medicine and corresponding treatments. It was during this time I realized what I wanted to do.”

He’s been connected with UConn Health Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine in some form ever since. The clinical chemistry residency was from 1978 to 1980, then he joined the UConn School of Medicine faculty as an assistant professor. He became an associate professor in 1986, full professor in 1994, and has been emeritus since his retirement from full-time service in 2021. He continued working part-time until December last year, and still is a regular in the lab, on his own time.

Hopfer’s leadership appointments over the course of his UConn Health career include associate director (1980), then director (1990), of the Division of Clinical Chemistry, director of the Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening Program (1993), the director of the John Dempsey Hospital Core Laboratory (1998), and the hospital’s point-of-care director (2006). He has been affiliated with the Association of Clinical Scientists almost every year since 1983, including a term as president 1994-1995.

His appointments outside of UConn Health include, among others: the World Health Organization, the Connecticut Department of Public Health, the Connecticut Poison Control Center, Connecticut’s Expert Genomics Advisory Panel, the Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Science, and the Cystic Fibroses Foundation Newborn Screening Quality Improvement Consortium. He still serves on the Commission of Medicolegal Investigations for the State of Connecticut.

Days before the 50th anniversary of his arrival at UConn Health, Hopfer reflected on his career with UConn Today:

What is it about UConn Health that’s kept you here for so long?

This was a good place to work and be productive. The department provided high-quality patient-oriented service and gave me the opportunity to follow academic pursuits. It was a smaller institution and I enjoyed the opportunity to interact with clinicians of multiple disciplines, the majority of whom I knew on a first-name basis. I was able to author or coauthor papers with colleagues in hematology, endocrinology, orthopedics, nephrology, etc., both inside and outside of the institution. based on these interactions I delivered papers in many countries. As an example, in 1989 I spent a week in Moscow writing a document with representatives from other countries on the toxicology of nickel for the World Health Organization. Another high point was the ability to inspect the neutrino chamber 6,800 feet below the earth’s surface in Sudbury, Ontario, Canada. So interactions at UConn Health and the School of Medicine took me on a journey to places I never thought I would ever go.

I was in the right place at the right time. Laboratory Medicine was just becoming a real discipline, especially for academic medical centers. John Dempsy Hospital was brand new. Since it was just opening the departmental faculty and the majority of the staff were my age. We had children close to the same time and we socialized together. As my daughter said when she was about 8 years old, UConn is my work family.

To this day you remain involved with national committees on newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. How did your leadership in this area come to be?

Newborn screening for CF was first offered as a supplemental test (not mandated by statute) at Saint Francis Hospital in the late 1980s. It was not, as yet, clear whether detection of an infant at birth was beneficial. Sometime in 1992 the pediatric cystic fibrosis center was moved from Saint Francis to the Department of Pediatrics at UConn Health. Coincidentally the first CF-causing mutation was just recently identified. At the request of the Department of Pediatrics and Genetics, with approval from Dr. Peter Deckers [then medical dean], we began investigation as to how to proceed. I spent a week at the University of Pittsburgh to learn how to perform molecular testing using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). When I returned, we hired staff and started a small laboratory in rented space on Farmington Avenue. First testing was performed on May 1, 1993.

Since screening for CF was still not mandated by statute, convincing Connecticut hospitals to send specimens was slow. We gave grand rounds to most of the hospitals in Connecticut and in some cases more than once. It took a while. Soon science began to indicate that identification of CF at birth significantly decreases mortality and morbidity. Since 2009, newborn screening for CF is mandated by statute in Connecticut. We presently screen 70% of infants born in Connecticut.

To show how things change over time, the testing currently includes a stepwise algorithm necessary because instead of one mutation causing CF there now are 1,084. The algorithm includes measurement of a protein increased in CF, a 60-mutation panel and next-generation sequencing which can identify 981 mutations. Our laboratory also performs the confirmatory sweat chloride test and provides genetic counseling for those with a positive screen by telemedicine with counselors located at the University of Florida.

You surely have seen a lot over 50 years at UConn Health. What are your observations?

Medicine has changed. The way you treat people has changed. The way you teach has changed. The way you look at disease has changed. Everything has changed.

To address these changes the laboratory also had to change. Similar to the example for expanded testing for CF most other diseases also require expanded testing algorithms, which in turn will help decide treatment options. A good example would be certain types of cancers where immunotherapy targets very specific mutations.

One of the high points for me was the ability to automate testing early on. In 1999 we began the process of automation in the main laboratory. We were the third clinical laboratory in the United States to automate routine testing. In the early days this was a hard sell to administration but today no clinical laboratory would be able to survive without some form of automation. Many tests would take up to two weeks to achieve results. Today for most acute care tests results are obtained in minutes. In 1975 it would take up to two days to rule in or rule out a myocardial infarction (heart attack) by laboratory tests. Today it takes approximately 10 minutes from the time we receive the specimen. We have an automation track that performs approximately 130 tests on a very small amount of blood very quickly.

You no longer have to keep showing up to work, but you do, on your own time. Why?

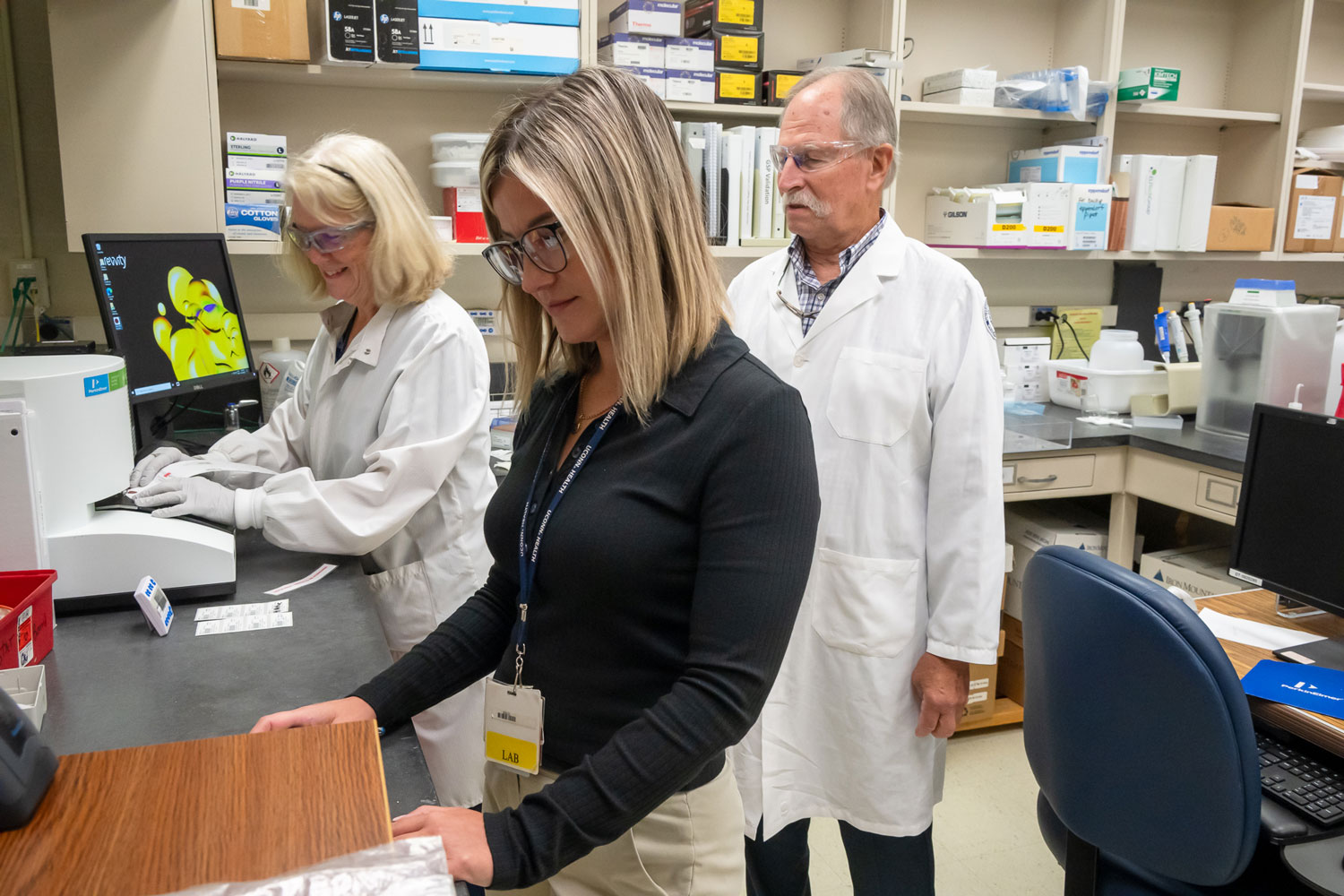

Having something to do that is meaningful and has purpose is important to me. It made more sense to volunteer doing things I know rather than things that just consume time. About five years ago the laboratory was very short staffed. The laboratory has been serving as a clinical rotation site for five students per year from the School of Allied Health on the Storrs campus. They have a very good medical laboratory sciences program. During the last five months of a four-year curriculum, students are placed in a clinical environment for on-the-job training. Until very recently we have offered employment to almost all of the students we trained, which helped to fill the staffing void.

All high school age students know what a physician and a nurse is but very few know what a medical laboratory scientist (MLS) is. It is a high-paying and rewarding career path. Most people are exposed to it, including me, by accident.

Working closely with the faculty of the MLS program at Storrs I have been attempting to educate high school age students and undecided students in the first two years of college to include MLS as another possible choice in a health-related career. For the last two years I have been going to high schools participating in presentations, career fairs, or any way I can get my foot in the door. Each presentation usually interests about five students, which we then arrange for a chaperoned visit with a detailed tour explaining the multifaceted duties of an MLS. The tour ends with a two-hour hands-on experience where the students perform simple laboratory tests and diagnose diseases based on the results they have obtained. This has been rewarding and successful in that of the 30 or so students who have participated, four have actually enrolled in the MLS program at Storrs.

After 50 years it remains rewarding to participate in some capacity at UConn Health. I have been a team member in providing above-average patient laboratory service to John Dempsey Hospital and UConn Health’s clinics. I have also participated in rewarding fruitful scientific endeavors. Attracting students into the field of medical laboratory science continues to be rewarding.

Alternatively, my daughter may be correct, and it is just difficult to leave my work family.

Latest UConn Today

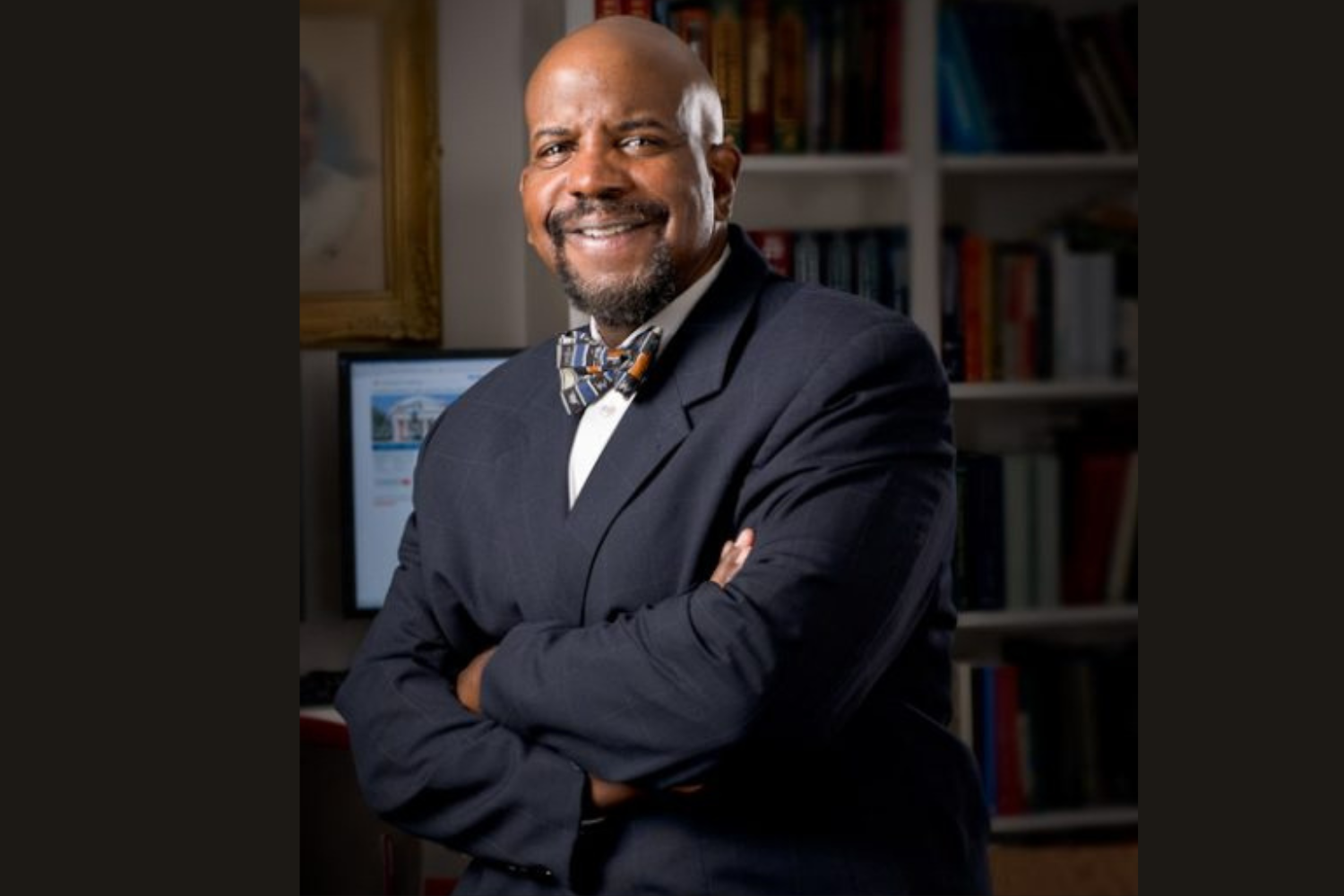

- Dr. Cato T. Laurencin Elected International Fellow of Chinese Society for BiomaterialsUConn's Sir Cato T. Laurencin's prestigious recognition honors the most distinguished scientists in the field of biomaterials around the world.

- Rebuilding Spines, Restoring Lives: How UConn Health’s Dr. Singh Helps Patients Stand Tall AgainRebuilding a spine is more than surgery, it’s restoring a life. At the Comprehensive Spine Center at UConn Health’s Brain and Spine Institute, Dr. Hardeep Singh specializes in complex spinal reconstructions that give patients like Tina and Julie the chance to stand tall again, walk without pain, and return to the lives they thought they had lost.

- State Investment in QuantumCT Supports Innovation InfrastructureGov. Ned Lamont announced that Connecticut will invest more than $50 million in New Haven to spur growth in cutting-edge sectors, including $10 million for QuantumCT, a statewide initiative led by UConn and Yale

- UConn Releases Annual Safety ReportsThe two reports are the Clery Annual Security and Fire Safety Report, and a report from the Office of Institutional Equity

- UConn Indoor Air Quality Initiative at the United NationsInitiative joins Global Pledge for Healthy Indoor Air

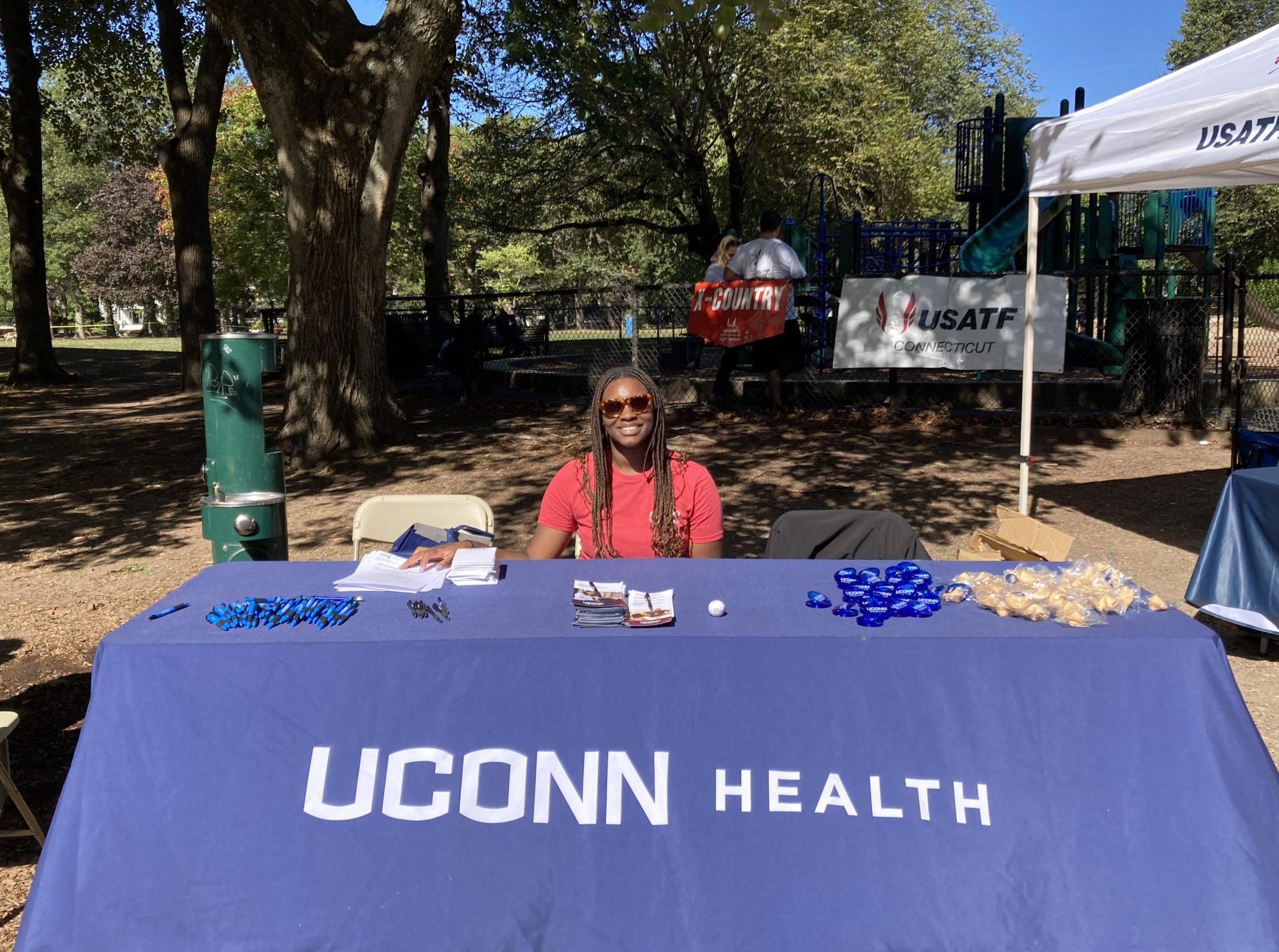

- New England Sickle Cell Institute Continues Raising AwarenessSeptember is Sickle Cell Awareness Month, and the Institute proudly participated in the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America’s New Haven community walk.