Cooperation and Competition: How Fetal and Maternal Cells Evolved to Work Together

The maternal-fetal interface is the meeting point for maternal and fetal cells during pregnancy. It’s been long understood as an area of conflict, where the placenta–a fetal organ– invades the mother to access nutrients.

This is an unusual situation because, in a normal case, foreign cells should be rejected by the immune system. During pregnancy, they are tolerated. However, mother’s cells also limit this invasion to an optimal state. The fight has continued for millions of years in evolution.

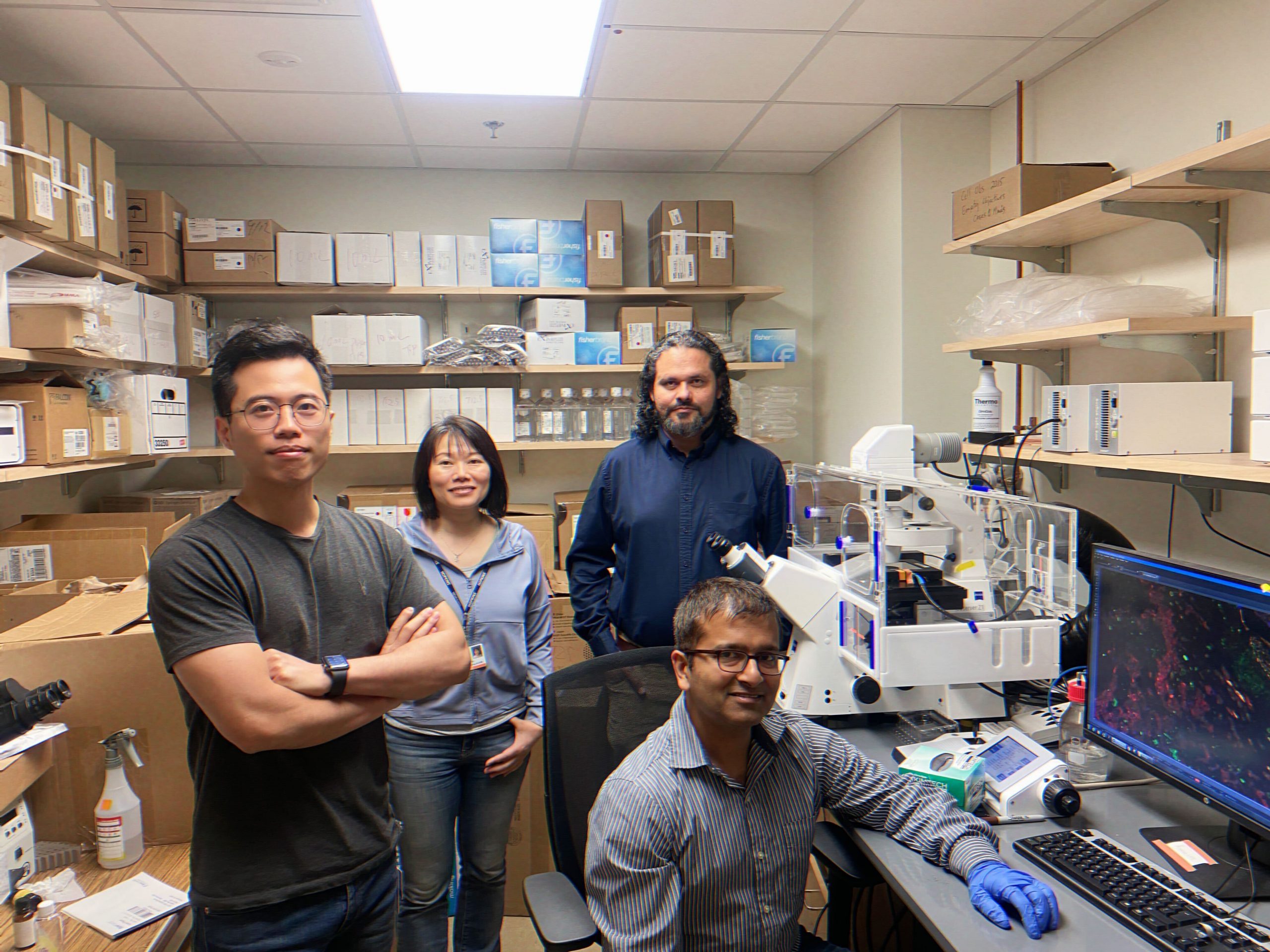

In the latest issue of the Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Kshitiz, associate professor of biomedical engineering at the UConn School of Dental Medicine, demonstrates that pregnancy is not solely a conflict between mother and baby, rather, a delicate balance of cooperation and competition that has evolved overtime to ensure a successful pregnancy.

Postdoctoral fellows Yasir Suhail and Wenqiang Du, along with Gunter Wagner at Yale and Junaid Afzal at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) also contributed to this research.

Wagner, former chair of evolutionary biology at Yale, and Kshitiz previously argued that there has to be cooperation between the mother and the fetus in order to sustain the pregnancy. Although the scientific discipline has mostly talked about genetic conflict, evidence of cooperation which modulates this conflict has been lacking.

“The maternal fetal interface, for this is what the placenta-uterus interaction is called, is like an unresolved frontier between countries. There is so much difference between different species, which is not found for any other organ,” said Kshitiz.

In anticipation of pregnancy, the endometrium undergoes a process called decidualization, the thickening of the tissue which women experience in each menstrual cycle. This process of deposition of matrix prevents excessive invasion by placental cells into the endometrium. Afzal and Du, demonstrated that placental cells influence the mother’s own cells to degrade their own matrix– a very surprising finding.

“It is this active persuasion by the placental cells which made the mother’s endometrial cells to reduce her own defenses by secreting a protein, which was so surprising,” Wagner said.

Suhail modeled the molecular interactions between placental and endometrial cells as an electric flow problem, identifying the key circuit underlying this manipulation.

“It is rare, and heartening to see such close integrated collaboration between computation, and experimentation. My model was created by experimental data, and the discovery was validated by experiments,” said Suhail.

In game theory, the mix of competition and cooperation is known as co-opetition. The maternal-fetal interface, the researchers found, is home to a myriad of cell interactions that embody the true meaning of co-opetition.

Kshitiz credits a conversation with an economics professor from the United Kingdom, Dr. Anshuman Chutani, who told him about the extensive literature in econometrics on co-opetition.

“It is a term which we gladly borrowed,” said Kshitiz. “It is not merely cooperation by the endometrium, but an induced cooperation between competitors.”

In the maternal-fetal interface, the fetal cells work to actively persuade maternal cells to stop building protective tissue so that fetal cells can effectively invade the placenta and retrieve nutrients. Crucially, this interaction does not happen alone—it depends on the mother’s cells own readiness to respond to signals coming from the placenta. This proves that placental invasion is more of a combination of competition and cooperation between maternal and fetal tissues, not simply an area of conflict as previously believed.

This discovery does not only shed light on pregnancy complications that involve problems with placental invasion, such as placenta accreta and preeclampsia, but may also have broader implications on cancer metastasis and understanding how certain cancers invade the body.

“This study, jointly conducted by scientists at UConn Health, Yale, and UCSF, can shift the way we think about conflict between the generations, right during when the fetus is still in mother’s womb,” said Kshitiz.

Latest UConn Today

- Making Strides, Breaking Records: UConn’s School of Pharmacy Places Second in the 2025 ACCP Clinical Research ChallengeThis past Spring, three UConn Pharmacy students showcased their grit and determination in the 2025 ACCP (American College of Clinical Pharmacy) Clinical Research Challenge, earning second place – the highest finish UConn has ever achieved in the competition.

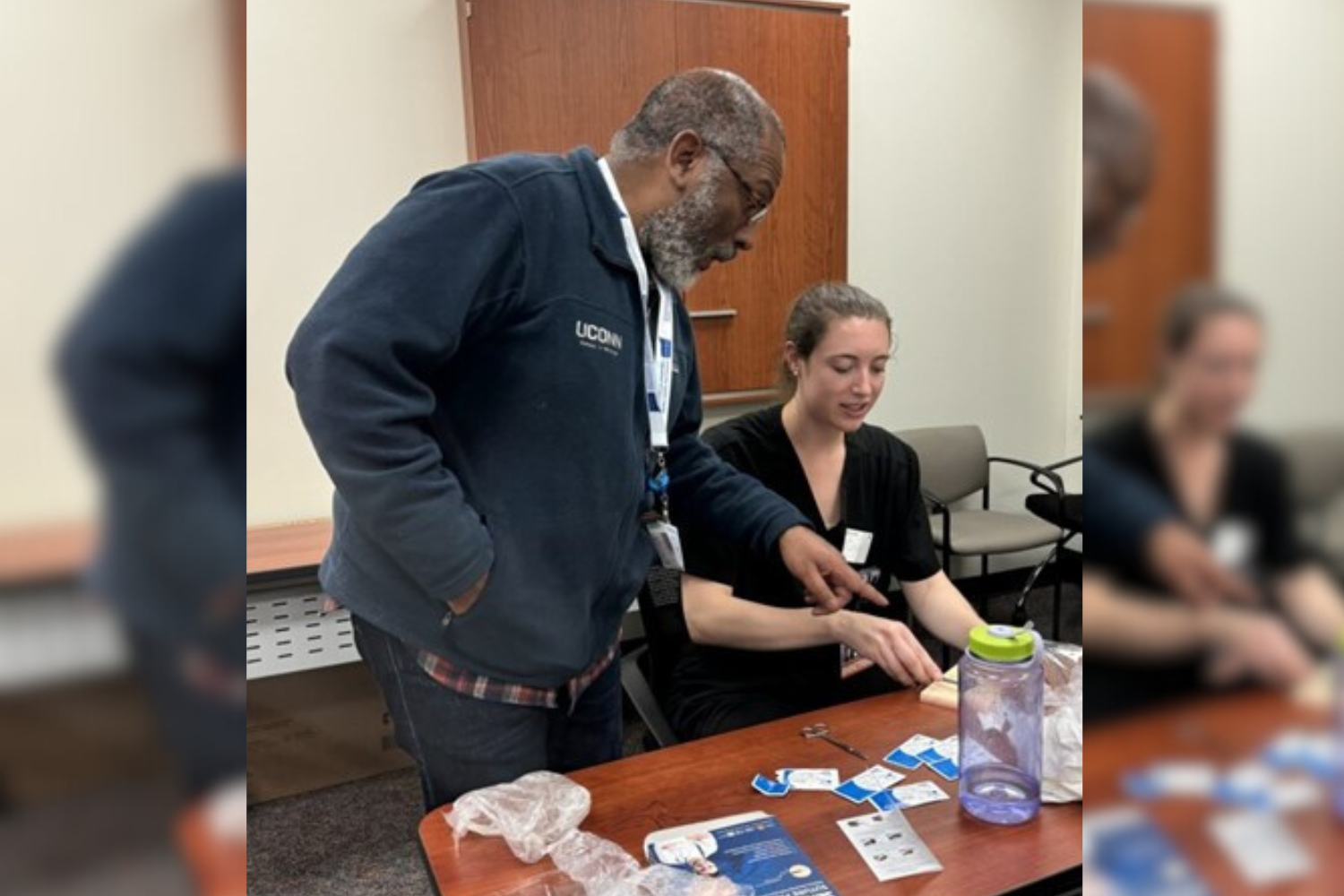

- Continuing Education for Health Professionals and Students at the Right Time, Right Cost, and Right Here!Health care professionals turn to the CT AHEC Network based at UConn Health to get the training and information they need to keep up to date.

- The Time to Act is NowUConn Health Disparities Institute Dr. Linda Barry brings expertise to state efforts responding to federal cuts to health care.

- The Cato T. Laurencin Institute Pre-K Award Program Graduates Another Successful CohortEstablished in 2014 by UConn Professor Sir Cato T. Laurencin, the Pre-K Junior Faculty Career Development Award Program is a pioneering two-year interactive award program.

- UConn Law Launches Graduate Certificate in Insurance LawThe program is open to individuals with a law degree, as well as students with an advanced degree in a related field and with significant legal or insurance experience.

- Damsels, Femme Fatales, and Queens of CrimeTwo UConn professors on the history of fictional female criminals and crime-fighters