Misunderstood Monsters: Tales of Horror Are Far More Than Blood Splatter and Gore

Phoenix Cardwell was around 8 years old when she first heard the story of the so-called Russian sleep experiment.

It’s a scary tale that circulated when she was in third grade about scientists who developed a drug to keep people from sleeping, only the side effects of such deprivation caused self-mutilation, essentially turning those taking the medication into zombies.

“The iconic photo that went along with the story is a creepy picture of an emaciated man sitting in bed, which later turned out to be just a photo of a Halloween prop, but it stuck in my head,” Cardwell ’26 (ENG) says.

For nearly a decade the image churned inside her, eventually twisting itself into an oil on canvas painting of a contorted creature that she titled, “I Have An Itch, Would You Like To Scratch It?”

“I hated hearing stories like that because they were so scary. At the same time, I wanted to keep hearing them,” she says. “‘Itch’ is from a series I did my senior year in high school when I was drawing things I didn’t want to see because they scared me but things that I was drawn to because they scared me – like itching a scab, you know you shouldn’t do it but it kind of feels good.”

Cardwell says she was raised on reruns of “The X Files” and “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” graduating to the 1979 and 1986 classics “Alien” and “Aliens” when she was older, and a miniseries like “Midnight Mass” as an adult.

The movie “Skinamarink” is the last one to get into her head. After watching it, her dreams spoke to her. “Look under your bed,” they warned, just like the father in the movie to his children. She looked once, maybe twice, that night.

“It’s interesting to see what movies scare people and what movies don’t,” she says. “I guess another part of why I like horror is because I like thinking about the psychology of it. You could do a little bit of a Freudian analysis of why something scares this person but not another.”

And even if Sigmund Freud isn’t explicitly on the syllabus in English professor Gregory Semenza’s class on horror, there’s still plenty to dissect in a genre that he says is “maligned and misunderstood, often reduced to blood splatter and gore.”

‘Horror can function as a kind of therapy’

Certainly, movies with titles like “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” come with a built-in warning that viewers will witness a certain amount of carnage and see quite a few dangling body parts, but Semenza says horror films are far more than that. They can be funny. They can be smart. They can be artful – and the scare factor is part of all that.

Since he was a child, Semenza has found comfort in horror films, and even says he’ll turn one on just before bed, much the same way a generation before him would turn on a spaghetti Western to wind down for the night.

But after spending the day navigating a hostile world and encountering bad news at almost every turn, many of his students, friends, and family might wonder why Frankenstein’s monster would have a calming effect after the sun goes down.

“There is an increasing collection of data providing at least one answer to this question, which is that horror can function as a kind of therapy,” he says. “It provides an adrenaline-pumping, frightening experience that is entirely safe, and when we experience it, we’re more prepared to face the horrors of the real world. Horror in doses may be an effective remedy against anxiety and certain levels of depression.”

Imagine turning to Michael Myers in “Halloween” to find solace.

Cardwell, who took Semenza’s class in spring 2023, says her friends on Halloween might enjoy the cult classic “Killer Klowns from Outer Space” because it’s packed with absurdist humor that would appeal to a mixed crowd, even as an innocent puppet show lures someone to their death and a man is electrocuted.

Laughing in the face of fear offers a catharsis, she says, and watching in a group, of course, takes off some of the edge.

“For the same reason people might love tragedies, the catharsis of crying with the character, horror can be similar. There’s no more stressful situation than whatever a horror movie character is going through,” she says. “It’s just a good release of emotions to watch a character go through that on screen.”

Terror vs. Horror

Mark Manson ’27 (ENG) used to cry at even the thought of something scary. “Jeepers Creepers” was far too intense – just having it on in the house caused him to shudder. He preferred that his older brother took the seat next to their father during movies like that. As time passed, though, his brother moved out, and Manson inched toward his father’s right.

“I started to see all the patterns that would happen in each film, and I’d think, ‘OK, I’m not scared anymore.’ Now if I do get surprised or if I see something that subverts expectations, I’m wowed,” he says.

What I want students to see is there is a real art to the best jump scares, and there are real formulas that are behind them. — Gregory Semenza, UConn English Professor

Manson, who’s taking Semenza’s class this semester and is turning an assignment on “Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror” into an honors conversion project, watched “Hereditary” with his father in a darkened room with surround sound turned on, fully immersed, and they both were terrified.

It’s a core memory that makes him smile despite having seen the on-screen family’s torment.

Semenza notes an oft-discussed difference between horror and terror, a distinction 18th century British novelist Ann Radcliffe attempted to define two centuries ago as she pioneered the Gothic novel.

“She was trying to distinguish between a shock to the body that sort of paralyzes us into inaction and freezes our cognitive faculties, which is horror, and something that heightens our cognitive faculties by putting us in a state of dread. The latter is what she calls terror. It’s more about tension and anticipation of what’s to come,” he says.

One might call it a “slow burn,” or the build up to the payoff scare or big scene, Manson says. That’s his favorite type of horror, movies that string along an audience before hitting them with a psychological thrill or gory, bloody mess.

He’s not squeamish, he says, and looks forward to seeing the special effects – the severed arteries and rolling heads. Watching the varied ways that horror storytellers kill off their victims is, well, enjoyable if only in appreciation of the creativity.

There’s an art to the jump scare, Semenza says, and each semester his students – 200 spread between two sections this fall, filled to capacity with over-enrollment requests routinely turned down – produce four-minute videos demonstrating their horror genius.

“A lot of modern commentators reduce horror to the jump scare, and what they’re thinking of are those manipulative jump scares that are caused by loud sounds. They’ve been referred to as ‘cattle prod cinema,’ like if someone walked up to you with a cattle prod and zapped you. You’re not responding to something artful. It’s just a physiological response to a stimulus,” he says.

“What I want students to see is there is a real art to the best jump scares, and there are real formulas that are behind them,” he continues. “The one in ‘Carrie’ is so influential, where the hand rises out of the grave after you think the film is over. That’s one of the first final-scene jump scares in horror cinema, and it’s really well done in terms of the way the hand pops out in a surprising location, even though you kind of know it’s coming, and the fact it happens about a beat earlier than you expect.”

Tame Horror as a Gateway

Tame Horror as a Gateway

Nicholas Sangiovanni, a Ph.D. teaching assistant in Semenza’s class, says his first introduction to horror, like many young children, was through the cartoon series, “Scooby-Doo, Where Are You!,” which often features a haunted house, situations that aren’t quite right, and at the end the revelation that the source of the fear is all man-made.

The formula is a replication of the earliest Gothic traditions, he says, those in English literature from the 17th and 18th centuries of ghost stories. By today’s standards, one might call black-and-white sitcoms like “The Munsters” or “The Addams Family” tame horror. Even Casper was labeled friendly.

“It’s fun. It can be goofy. It can be very charming, and it can also be heartwarming to a degree. These kinds of shows are a great way to show people that fear, of course, is central to the idea of horror but it’s not the only way to think about what horror is, what’s the point of it, or what makes it important,” he says.

Sangiovanni goes on to note that the word “horror” comes from the Latin “horrere,” which means “to shudder,” and “monster” comes from the Latin “monstrum,” meaning “a warning or omen.”

“Monsters are a great way in horror to consider what people think about themselves and what they value,” he says. “You can answer those questions very expediently by looking at the things they’re afraid of and the monsters they create. What do those monsters look like? As much as I love what we would now call psychological horror or horror thrillers, I’m a monster person at heart. I love a good creature.”

Some of the most memorable: Swamp Thing. Creature from the Black Lagoon. Bride of Frankenstein. Dracula. The Thing. Alien. Jaws.

Wait, Jaws?

Semenza says the Steven Spielberg classic filmed on Martha’s Vineyard 50 years ago is among the best horror films ever made, precisely because the shark doesn’t act like a normal shark.

“It clearly possesses a higher level of consciousness,” he says. “It’s sentient in a way that suggests awareness and even a capacity for revenge and rage, so the shark’s behavior exceeds anything we would consider to be scientifically accurate, and, in that way, it falls into the conventions of a typical horror narrative.”

The iconic jump scare when Hooper encounters Ben Gardner’s severed head still gets audiences who’ve watched the film over and over through the years.

“I always tell my students the building up of a great jump scare or great scare in general is a lot like the building up of a joke. It’s this process of accumulation that eventually has a punchline and allows for a sigh of relief. Once it’s over we can exhale,” he says.

‘It’s not all about scaring or being scared’

But as long as that little Leprechaun is running around, the one from the movie her parents watched a long time ago that prompted her to run to her bedroom and hide, Shelby Kreiger ’24 MA, Cert. can’t bring herself to exhale.

It still scares her to this day, although now she watches with delight films like “Rosemary’s Baby” and “Diabolique.”

Over time, she’s learned to appreciate horror: for the scares, yes, but also for the stories it tells – stories of human experience, with allegorical meanings behind its monsters and villains.

“‘Night of the Living Dead’ deals with human issues. There’s racism, there’s sexism, there’s misogyny, and there’s the idea of things that we’ve just lived through, like viruses and pandemics,” says Kreiger, a Ph.D. teaching assistant in Semenza’s class.

“We can relate to these things. Horror is relatable. It’s not all about scaring or being scared, torture or gore. Not all of it is so extreme. A lot of it can be slow-paced, really psychological, really existential, and teaching us a lot about ourselves,” she adds.

There are many horror films in which gore is implied, the act of violence happens away from the audience, she says, but just the thought is enough to give viewers a scare and allow their imaginations to run wild.

Movies from the “Saw” franchise though, while pleasurable viewing for some, aren’t on her must-watch list, she says, mostly because she’s not interested in watching that kind of terror.

Even scholars like Semenza have certain films they wished they didn’t see or certain topics they’d prefer to avoid. Films about home invasions or nuclear annihilation are too close to home for many viewers, he says, and he typically won’t assign them in class.

“Nevertheless, the concept of a film traumatizing someone tends to be overstated,” Semenza says. “What most of the empirical research shows is that if you have experienced real trauma in your life, anything that causes repetition, dwelling on it, thinking about it, the memory of it, can possibly cause a negative reaction. But that preexisting trauma has to exist. You’re not going to watch something and, with no history of trauma, be psychologically damaged for the rest of your life.”

Almost As Old As Time

Semenza started his career as an English professor teaching and studying classics from William Shakespeare and John Milton, turning students skeptical of literature from the 1500s and 1600s into lovers of stories like “Much Ado About Nothing” and “Paradise Lost.”

Later, seeing those stories retold in modern-day film – the Shakespearean pastoral comedy “As You Like It” influencing the birth of what today’s audiences know as the rom-com, for instance – gave him a bridge from the written word to the big screen, and that lifelong intellectual interest in horror allowed him to pivot his research.

“There’s just tremendous beauty and art and intelligence behind the greatest films in any category,” he says. “Horror is more vilified than some of the other genres, though the rom-com is similarly misunderstood and misrepresented. The musical, too. Why do so many critics plug in the worst horror films for all horror when we talk about this particular genre?”

After all, Shakespeare’s first tragedy, “Titus Andronicus,” portrays some of the grisliest body horror, he says, shocking even by modern standards. And “King Lear” forces an audience to endure the blinding of Gloucester at the hand of Cornwall.

“What Shakespeare seems to be saying is the audience needs to see this horror. It needs to experience it,” Semenza says. “And then a few decades later, Milton creates his character of Satan, one of the original great horror villains, the monster who seduces us to enter a world of sin and darkness – but also one of forbidden pleasures. The texts I study are not detached. They’re part of a continuum that goes back to the ancients.”

Latest UConn Today

- Meet Jean: A Lifetime Giver on a Mission to Always Help OthersJean Martin has enrolled in a new UConn Health clinical research study to help enhance the future care of sickle cell disease patients.

- Professor: Supply Chain Management Can Strengthen Connecticut’s Vital Manufacturing SectorIn Connecticut, the demand for supply-chain managers has increased 52% in the last five years

- UConn John Dempsey Hospital Recognized for Exceptional Clinical PerformanceSepsis, pneumonia, hip fracture care, and GI surgery earn 5 stars from Healthgrades

- Being Seen, Feeling Seen: Summit Examined Complicated, Far-Ranging Intersections of Sport and Human RightsHuman Rights Summit features perspectives from athletes, academics, and industry experts

- Protein Powders and Shakes Contain High Amounts of Lead, New Report Says – A Pharmacologist Explains the DataPowder and ready-to-drink protein sales have exploded, reaching over US$32 billion globally from 2024 to 2025. Increasingly, consumers are using these protein sources daily.

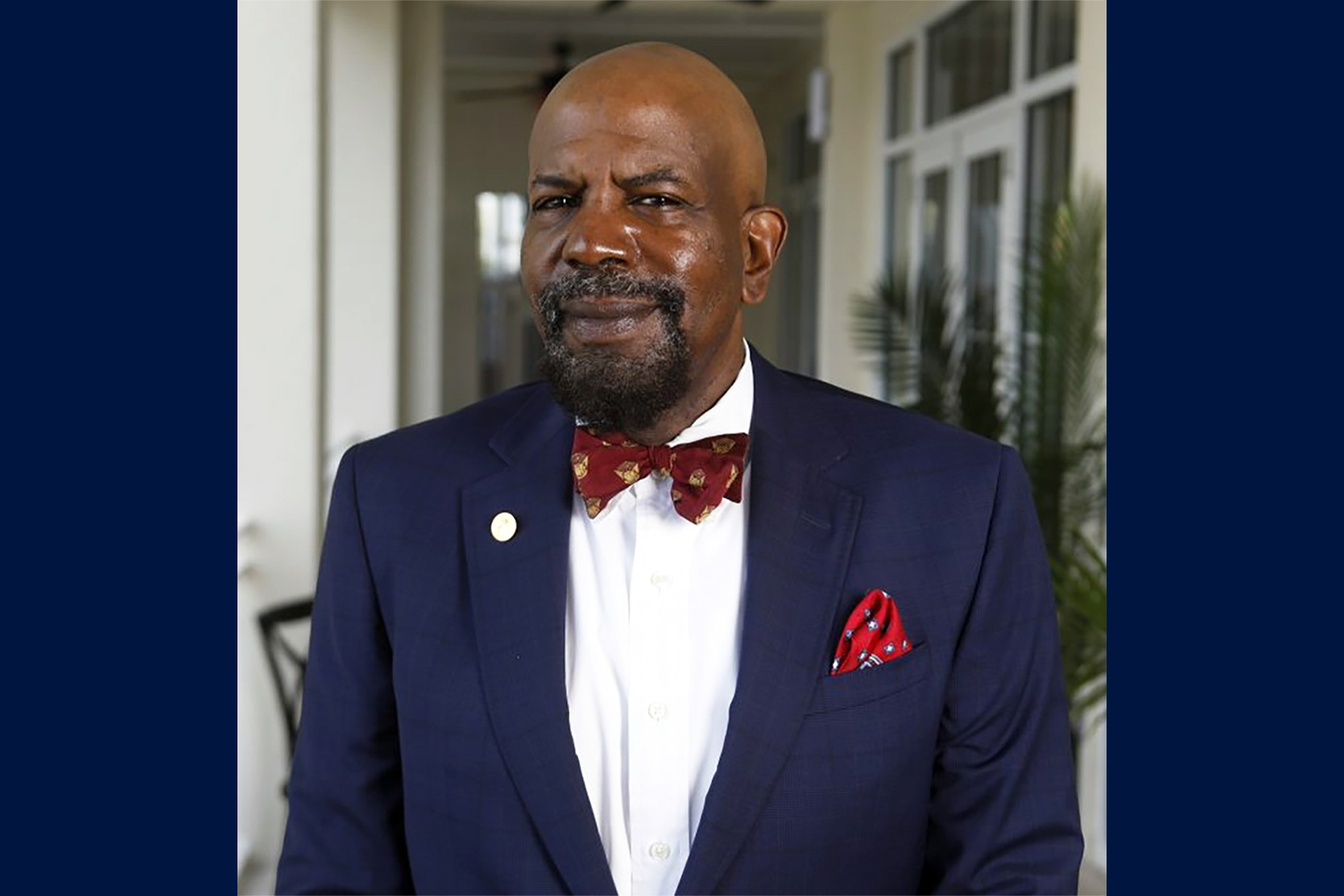

- Professor Sir Cato T. Laurencin is Plenary Speaker at AAMP ConferenceUConn Professor Sir Cato T. Laurencin was the Plenary Speaker at 39th Annual Association for Academic Minority Physicians, Inc. Conference in Alexandria, VA.