Research Study Analyzes How Human Rights Content Empowers Spanish Heritage Learners

In a Connecticut high school Spanish heritage language classroom, the conversation moves well beyond verb conjugations and vocabulary lists. Students are debating labor laws, analyzing fairness, and connecting their own lives to the experiences of migrant youth.

The catalyst for these conversations was a nine-week unit on migrant labor rights, designed specifically for Spanish heritage language learners at East Hartford High School. The unit became the focus of a research study co-led by Neag School associate professor Michele Back and East Hartford teacher and Neag School alumna Amber Dickey ’16 (CLAS), ’16 (ED), ’17 MA.

Their collaboration, the results of which were recently published in Foreign Language Annals, emerged from Dickey’s participation in UConn’s Human Rights Close to Home (HRCH) program, a professional learning initiative created by the University’s Dodd Human Rights Impact Programs in collaboration with the Neag School.

Dickey, a former student of Back’s, had long envisioned weaving human rights education into her Spanish heritage curriculum. When a call for submissions went out for a special journal issue on innovative language instruction, Back immediately thought of her former advisee’s classroom.

“We had always talked about collaborating,” Back says. “Amber was instrumental in launching the Spanish for Heritage Language program in her school, and when I saw she was incorporating human rights content, I knew it could make for a compelling study.”

Building a Curriculum Around Rights and Realities

As the architect of East Hartford’s Spanish heritage curriculum, Dickey had the flexibility to design units that prioritized both language development and meaningful content. Human rights education felt like a natural fit.

“It’s interdisciplinary, relevant, and encourages empathy, critical thinking, and civic awareness,” Dickey says. “By framing literacy instruction around real-world issues like labor rights and gentrification, students are not only improving their language skills but also engaging with authentic topics that impact their communities and beyond.”

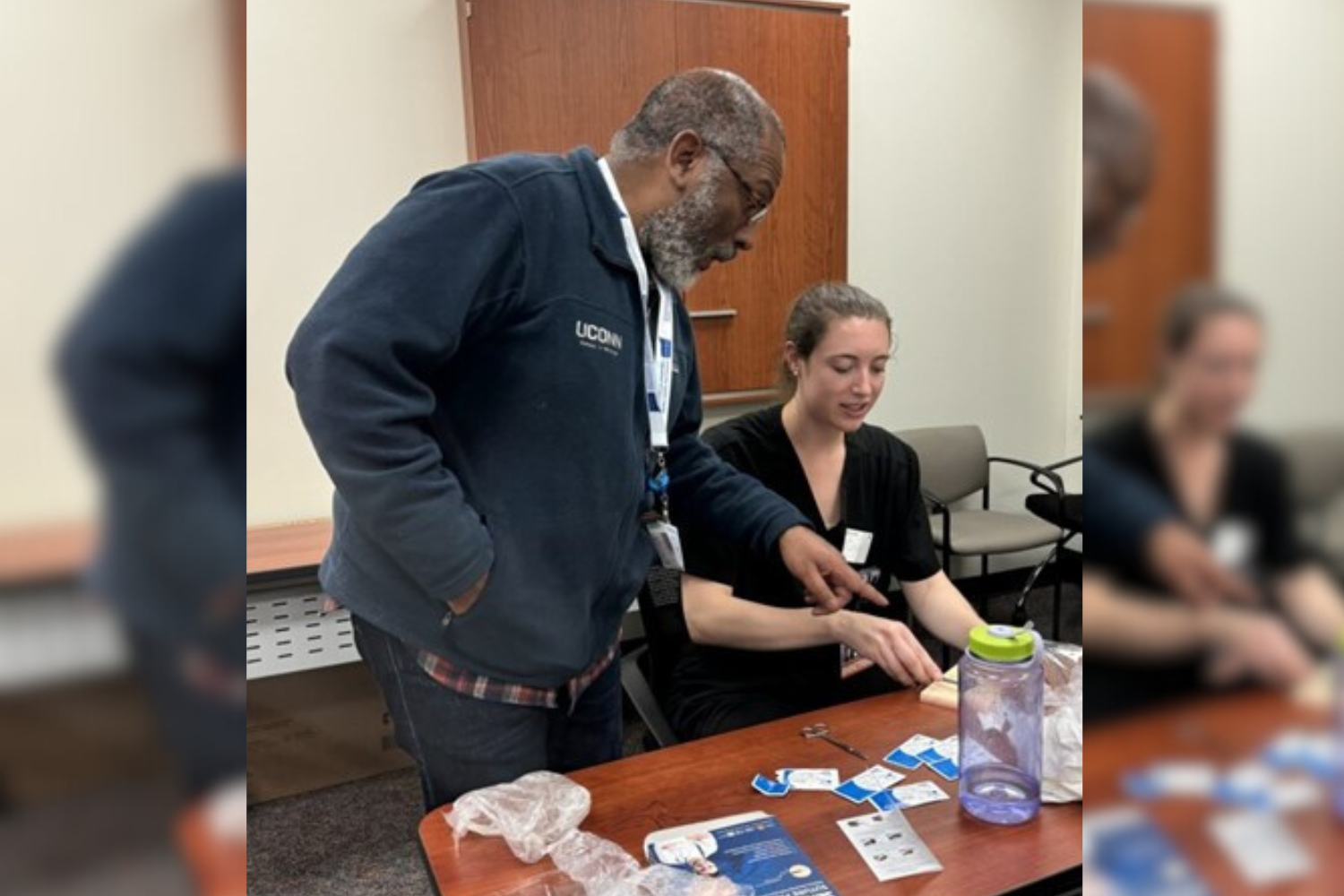

When the HRCH program opened applications to teachers in select districts, Dickey jumped at the chance and became a member of the first cohort in 2023.

“After reading the email, I knew this was exactly the kind of professional development I needed,” she says. “The UConn program gave me expert support, resources, and thoughtful feedback that helped me fully integrate human rights into my curriculum.”

The UConn program gave me expert support, resources, and thoughtful feedback that helped me fully integrate human rights into my curriculum. — Amber Dickey ’16 (CLAS), ’16 (ED), ’17 MA

The nine-week unit on migrant labor rights, held in the fall of 2024, grew from an existing text in her course: “Cajas de carton” by Francisco Jiménez, a semi-autobiographical account of child migrant labor. Dickey expanded the unit with the documentary “The Harvest / La cosecha” and research on Connecticut teen labor laws, encouraging students to analyze labor rights across historical and contemporary contexts.

“They were shocked to learn that kids as young as 14 can work on farms in Connecticut,” Back says. “That sparked debates about fairness and what children should be allowed or expected to do.”

Dickey’s classes were made up mainly of Latino students from Puerto Rico, Mexico, and Central and South America, many of them recent arrivals. While none were currently working in migrant labor, some were holding part-time jobs — and even full-time hours — outside of school.

“She asked them how many hours they worked, and some said they were putting in 40 hours a week on top of school,” Back says. “That was eye-opening, not only for them but for their peers.”

Dickey’s lessons were highly interactive. Each class began with a warm-up — an image, quote, or question to prompt reflection — followed by small-group reading and discussion. Students paused to unpack cultural references, historical moments, and key vocabulary before connecting the literature to articles from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“My role leans more toward facilitator than lecturer,” Dickey says. “This layered approach helped students move from literary analysis to real-world application, fostering awareness of their rights and responsibilities as young people and workers.”

The mixed-methods study by Dickey and Back used classroom observations, student surveys, and discourse analysis to explore how the unit affected student engagement, empathy, and civic awareness. Quantitative surveys showed only modest changes in those areas, but Back cautions against reading too much into the numbers.

“High school students can be difficult to survey,” she says. “We kept it short, but we still ran into survey fatigue.”

In the classroom, the picture was different. Observations captured students debating, challenging one another to provide evidence, and engaging in nuanced discussions.

“One student asked another, ‘Where’s your evidence for that?’” Back says. “That kind of rhetorical strategy wasn’t even part of the curriculum — it grew organically from the content and Amber’s teaching.”

Dickey also noticed a shift. Students began asking deeper questions about systems and policies affecting workers today. Months after finishing the unit, several had enrolled in UConn’s Early College Experience human rights course, citing the class discussions as the reason.

“Many expressed a stronger sense of empathy and solidarity,” she says. “Some saw themselves not just as students but as people with a voice in civic matters.”

Teaching Complex Issues

Introducing topics like labor laws and human rights declarations to high school students, especially multilingual learners, comes with challenges.

“Some students struggle to see the relevance at first, especially when the language feels formal or distant,” Dickey says. “I had to work intentionally to make the content feel personal and urgent — connecting it to their own experiences as workers, students, and members of immigrant communities.”

Once those connections were made, engagement often followed. Back praised Dickey’s ability to scaffold content without diluting its complexity.

“Her classroom was very active,” Back says. “Students prepared the content, reacted to it, debated it, and wrote about it. It was student-centered in the truest sense.”

The partnership between Back and Dickey reflected mutual respect and shared goals. The two first worked together in 2015, when Dickey was an undergraduate student and Back served as her advisor.

“Michele brings deep academic expertise and genuine respect for classroom practice,” Dickey says. “Her feedback helped me see patterns in student work and refine my instructional strategies.”

Back, in turn, values co-authoring research with teachers.

“They know what’s happening on the ground,” she says. “Working together leads to stronger research and better teaching.”

Ultimately, when students feel the content connects with their lives and communities, they become more engaged, more thoughtful, and more prepared to advocate for themselves and others. — Michele Back, associate professor

Both educators see potential for similar units in other heritage language programs.

“Human rights education fits naturally within any heritage language program,” Dickey says. “Students are already navigating questions of identity, culture, and belonging. Embedding these themes strengthens language skills and empowers students to engage critically with the world.”

Given current political debates over immigration, labor rights, and equity in education, she believes such a curriculum is more important than ever.

“It equips students to analyze these issues through informed, empathetic, and justice-oriented lenses,” she says. “It fosters civic awareness, amplifies student voice, and helps young people see themselves as active participants in shaping their communities.”

Back hopes to expand the study to a yearlong curriculum and track long-term effects. She also sees opportunities for scaling the work through partnerships between schools and universities, or professional learning initiatives like HRCH.

“Ultimately, when students feel the content connects with their lives and communities, they become more engaged, more thoughtful, and more prepared to advocate for themselves and others,” Back says. “That’s the kind of education that sticks.”

For more information on the Human Rights Close to Home initiative, visit humanrights.uconn.edu/hrch

Latest UConn Today

- UConn Once Again Ranks High in SustainabilityCampus engagement and planning efforts give UConn a sustainable edge

- How Will Cuts to SNAP Funding Impact Connecticut?Three UConn experts who have worked for decades to provide nutrition education through SNAP share insights on what cuts could mean for residents of our state

- Daniel Sullivan Named New Sr. Associate Vice President for Health Giving at the UConn FoundationThroughout his career, Sullivan has raised more than $100 million in support of transformational initiatives

- Making Strides, Breaking Records: UConn’s School of Pharmacy Places Second in the 2025 ACCP Clinical Research ChallengeThis past Spring, three UConn Pharmacy students showcased their grit and determination in the 2025 ACCP (American College of Clinical Pharmacy) Clinical Research Challenge, earning second place – the highest finish UConn has ever achieved in the competition.

- Cooperation and Competition: How Fetal and Maternal Cells Evolved to Work TogetherStudy published in PNAS reexamines the dogma of genetic conflict in the maternal-fetal interface

- Continuing Education for Health Professionals and Students at the Right Time, Right Cost, and Right Here!Health care professionals turn to the CT AHEC Network based at UConn Health to get the training and information they need to keep up to date.