Tagging Time Travelers

Horseshoe crabs hold the world record for surviving the longest without any significant changes to their body structure. Virtually unchanged for over 450 million years, they’ve earned the nickname “living fossils.” Another reason why this species remains so captivating lies in its molecular makeup – horseshoe crab blood is an almost iridescent blue and has been used as a key ingredient in developing vaccines and medicines for over 50 years.

Kate Castellano, a marine genomicist and assistant research professor in the Institute for Systems Genomics, is an expert on the genetics of these bizarre creatures. Along with UConn postdoctoral researcher Michelle Neitzey, Castellano published the first chromosome-level genome assembly for horseshoe crabs in February of this year.

Horseshoe crab blood is blue because it uses copper (instead of iron, like human blood) to carry oxygen, Castellano explains. It also has one incredibly special defense mechanism.

“Horseshoe crabs have cells called amebocytes that act like a built-in alarm system against gram-negative bacteria, which are also known as bacterial endotoxins,” Castellano says. “When they detect harmful bacteria, the blood thickens – almost like bubble gum – to trap the invaders and protect the horseshoe crab.”

This thickening property can also be used by medical researchers to screen for bacteria outside the crab itself. Around the 1970s, researchers used horseshoe crab blood to develop something called a limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) test, which can screen injectable drugs, vaccines, and medical implants for any harmful bacteria before they are administered to patients.

Currently, the main method used to create the LAL test involves extracting blood from live horseshoe crabs. Somewhere between 15% and 30% of crabs die during the harvesting process; for the ones that survive, it is difficult to monitor their wellbeing after they are bled and returned to the ocean.

After persevering for over 450 million years, these living fossils are now facing large population declines. They are currently listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, which tracks endangered species status across the globe.

“We think part of the reason that their populations are declining is because we harvest them for the LAL test and use them as bait, although we’re still unsure what else may be contributing.” Castellano says. “This is why tagging efforts to track their population changes and monitoring genetic shifts are very important.”

Conservation on the Coast

To keep animal research alive while also preserving the crabs’ population, Castellano and Neitzey collaborated with Sacred Heart University’s Project Limulus, a long-running ecological and conservation study of horseshoe crabs on the Long Island Sound, to help tag horseshoe crabs. Project Limulus Horseshoe Crab Tagging allows researchers to keep track of the populations in New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts and compare numbers annually. It also allows scientists who collect samples from the crabs to keep track of their well-being.

This year’s event was held on June 13th and included residents of Sherwood Island State Park in Westport, and volunteers from the UConn Genome Ambassadors Program, with as many as 40 individuals who signed up with Castellano. Project Limulus volunteers taught attendees how to conduct field surveys, assess overall health of the horseshoe crabs, identify sex and attach a Wildlife Service Federal disc tag. This event encouraged individuals to not only help tag but also understand the ecology of horseshoe crabs. Additionally, Castellano and Neitzey talked about the importance of using genomic data in combination with ecological data to aid species conservation.

During this event, volunteers were able to successfully tag over 50 horseshoe crabs this year.

“Project Limulus said it was their best event of the year — that was the highest number of crabs they had identified at a single event,” says Castellano. “I think it was because everyone was just so excited to be out in the water, finding them left and right.”

Castellano hopes to continue her collaboration with Project Limulus in future years, creating more tagging opportunities for UConn students, faculty and staff and to expand her research by digging into the genome of these curious crabs.

Latest UConn Today

- Mariah Klair Castillo ’24 MA: Finding a Voice as a Special Education TeacherCastillo originally worked in the insurance industry but always dreamed of teaching

- Getting Cozy: UConn Entrepreneur Focuses on Mindful Productivity as Werth Institute Program Continues Engaging First-Year Women'Take every opportunity you’re given and just make sure that you’re loving what you’re doing, that you want to be here, that you want to learn'

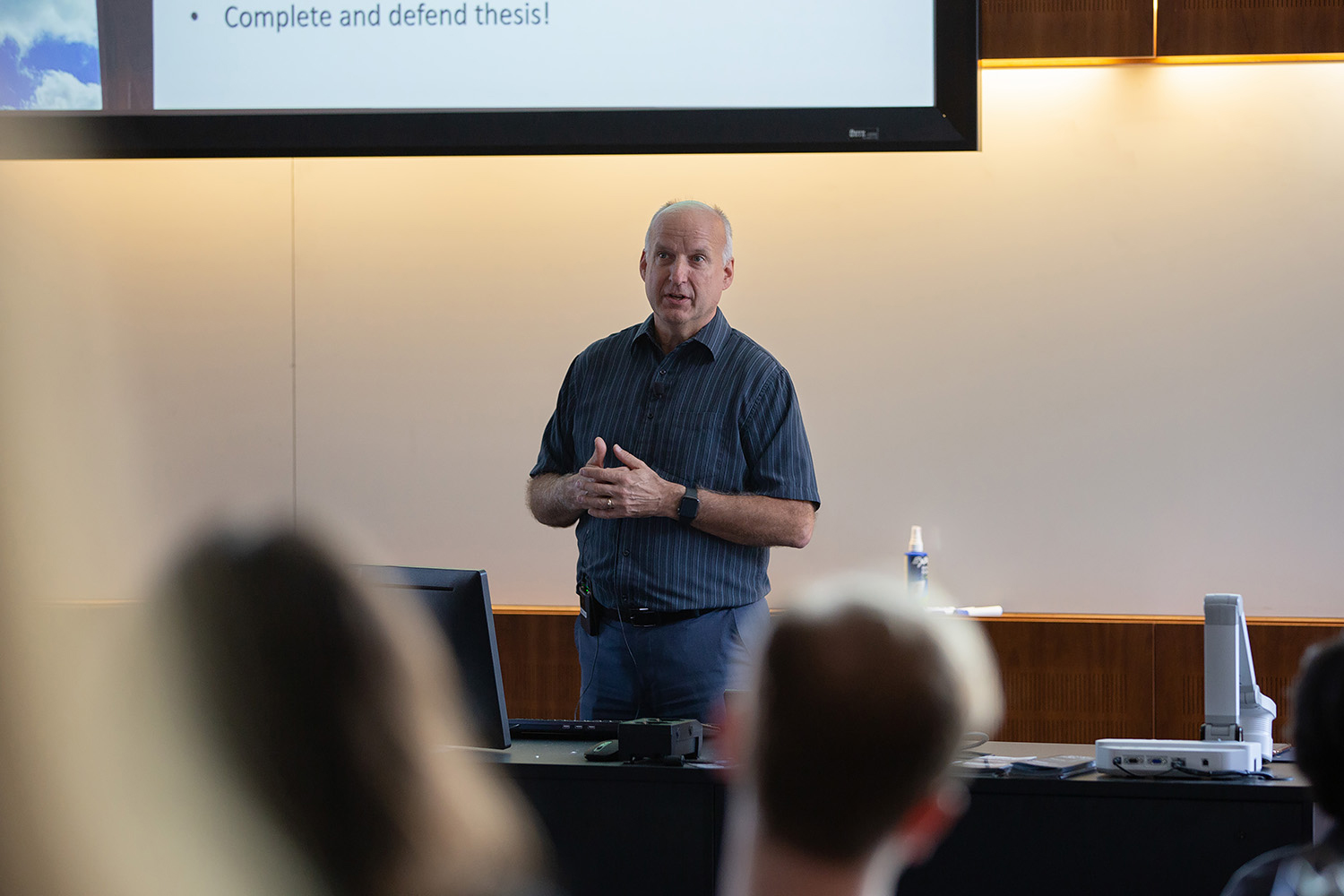

- Randy Walikonis Encourages UConn Students to Push Boundaries of KnowledgeAs UConn's biology majors continue to grow, the new head of the Department of Physiology and Neurobiology aims to expand hands-on opportunities while preparing students for research and medical careers

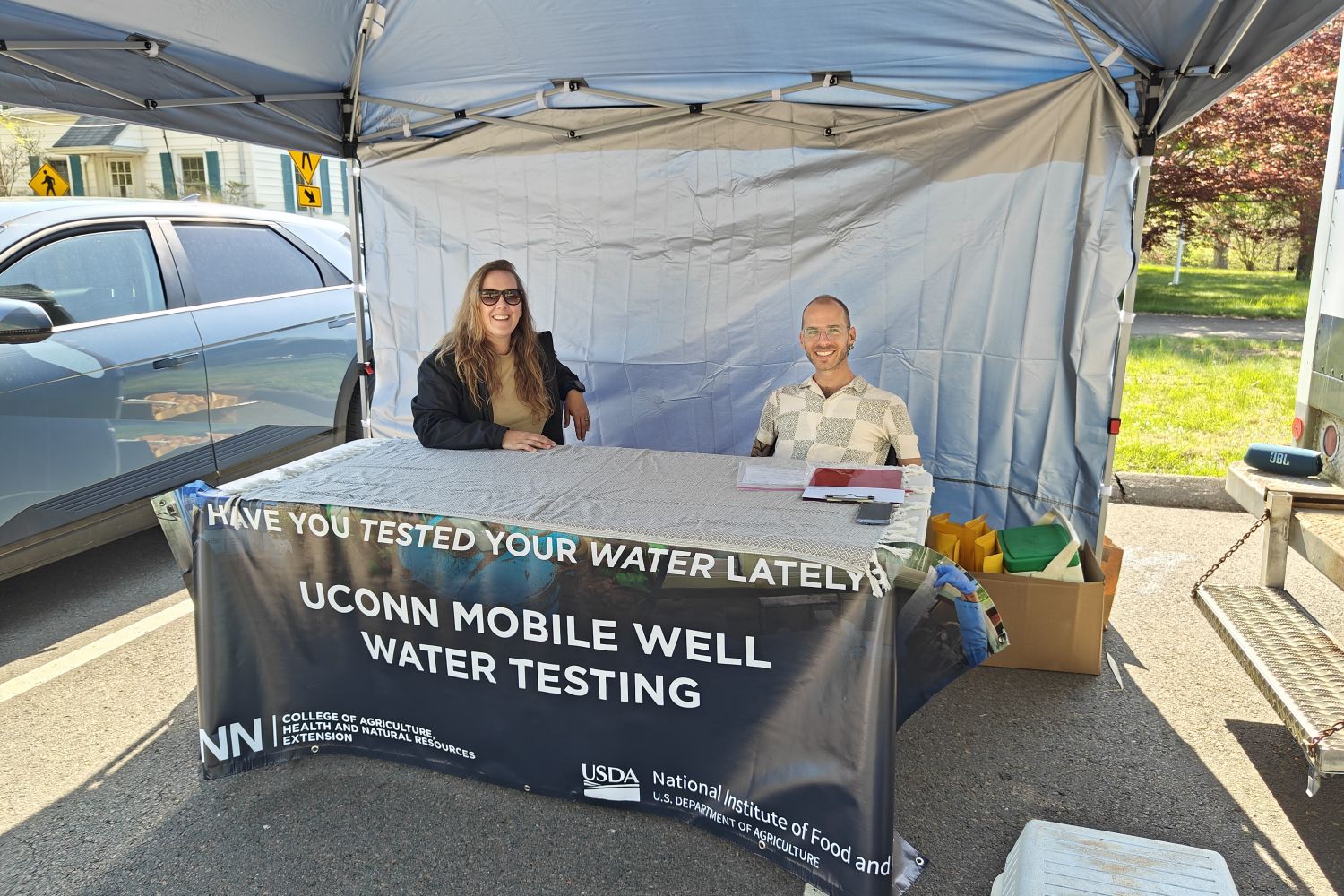

- Ripple Effect: The Collective Power of UConn Extension’s Water ProgramsFrom low-cost well water testing to reducing environmental threats to water safety through informed land use, UConn Extension programs seek to keep Connecticut's water clean and healthy

- UConn to Test Campus Emergency Systems on TuesdayUConn will conduct its Fall 2025 emergency alert system test on Tuesday, September 9

- Building Recovery Through Housing: SSW Awarded $1.6M to Evaluate Statewide HERO ProgramHERO acknowledges the link between stable housing and successful recovery for those who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness and are living with substance use disorders