UConn AUKUS Scholars Explore Undersea Vehicle Technology, International Collaborations in Australia

When biomedical engineering major Benjamin Fieldsend ’27 (ENG) was growing up in southeastern Connecticut, submarines were a regular sight on the Thames River. Living just minutes from the 687-acre Naval Submarine Base New London—and interning there in high school—sparked a fascination with the powerful, stealthy vessels that shape global security.

“Being part of a Navy community and seeing submarines in person gave me a real appreciation for the engineering behind these vessels,” Fieldsend says. “I’ve always been fascinated by how they’re designed and built.”

That early interest led Fieldsend to apply for the AUKUS Scholars Program, a new international initiative run through the National Institute for Undersea Vehicle Technology (NIUVT), where he and four fellow UConn engineering students explored the future of undersea vehicle technology—and the partnerships driving it—during a two-week academic exchange in South Australia and Tasmania.

“I thought [the program] was a unique opportunity to gain hands-on experience in an engineering field I wanted to explore more deeply,” he says. “As a BME major, I saw it as a chance to broaden my perspective and learn about systems that fall outside my usual discipline.”

A Trilateral Partnership

AUKUS—short for Australia–United Kingdom–United States—is a trilateral security partnership formed in 2021 to deepen defense cooperation between the three allied nations. In Australia, the program enjoys wide public support, seen as key to national defense as regional security dynamics in the Indo-Pacific grow increasingly complex. By gaining access to U.S. and U.K. nuclear submarine technology, Australia can increase patrol duration and coordination with allies.

NIUVT, co-directed by UConn Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Rich Christenson and URI Professor of Ocean Engineering James Miller, is uniquely situated to facilitate global training and research collaboration through AUKUS due to its established success in creating and developing research areas aligned with the strategic needs of the U.S. Navy, Christenson says. The institute’s research areas include acoustics, sensors, and signal processing; advanced materials and structures; advanced manufacturing processes; cybersecurity; human factors; marine hydrodynamics; propulsion enabling technologies; structural integrity, vibration, and control; systems engineering/modeling; unmanned underwater vehicles; underwater energy systems; and underwater shock.

As AUKUS Scholars, the students shared their knowledge on these research areas while learning from their overseas peers.

“Collaborating across borders is a tremendous asset—not just in advancing research, but also in strengthening peacekeeping efforts and fostering a more connected and cooperative world,” says Lisa McAdam Donegan, NIUVT Global Programs director, research coordinator, and UConn adjunct faculty.

An Interdisciplinary Engineering Experience

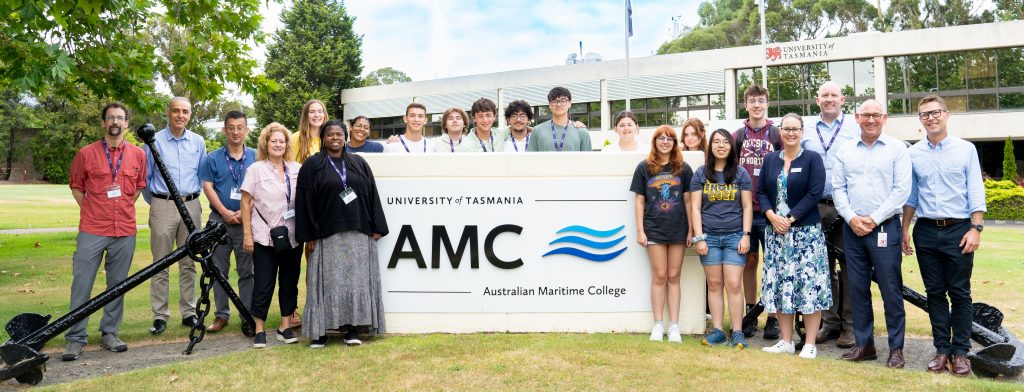

The U.S. cohort included Engineering students Fieldsend, Alyana Martinez ’28, Kate Marquis ’27, Zack Shepard ’27, and Ronan Allison ’27, alongside five peers from the University of Rhode Island. The second-year students in the Colleges of Engineering at UConn and URI were selected through an application process that included academic performance, an interest in STEM, and possessed a relevant background to support participation in student engineering competitions.

“Undersea vehicle technology is one of the most interdisciplinary fields in engineering,” says Christenson. “You need mechanical engineers for propulsion and pressure resistance, electrical engineers for power and control systems, computer scientists and programmers for autonomy, materials scientists for corrosion-resistant hulls, and even marine biologists and oceanographers to understand the environment these vehicles operate in. No one person or discipline can do it alone—collaboration is absolutely essential.”

Before traveling, they completed six weeks of preparatory seminars and toured the USS California, a nuclear-powered fast attack submarine in Groton. And then they began the approximately 22-hour flight to their overseas destination.

Once abroad, the scholars visited three universities with leading programs in maritime technology: The University of Adelaide in South Australia, Flinders University in South Australia, and the Australian Maritime College at the University of Tasmania in Tasmania. They participated in technical lectures, collaborative design projects, and lab tours—all designed to expose students to the systems thinking and interdisciplinary teamwork essential in modern undersea vehicle development.

“The areas we visited in South Australia are very similar to what we have here in southeastern Connecticut and Rhode Island, where the region represents the submarine capital in our part of the world,” Donegan explains.

The Visits

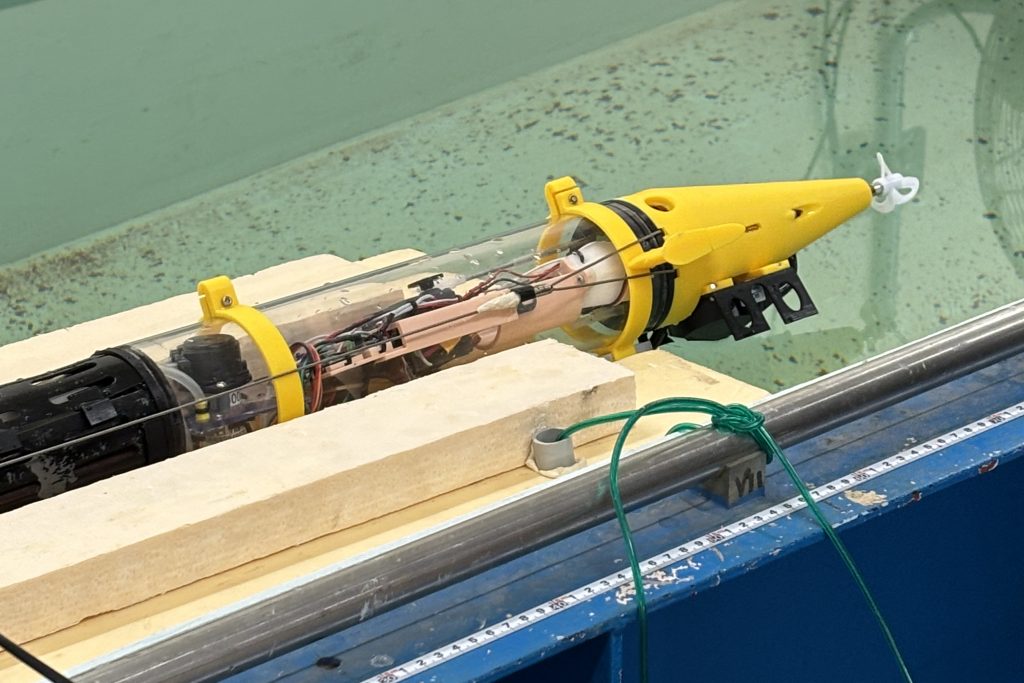

At the University of Adelaide, the Scholars toured the Shipbuilding Hub for Integrated Engineering and Local Design (SHIELD), a premier naval engineering center. There, Adelaide students presented their custom-designed submarine, which will compete in the International Unmanned Submarine Race in the U.K. in 2026.

To apply their own engineering knowledge, the AUKUS Scholars were challenged to design efficient small-scale propellers for model submarines. Their designs were 3D printed and tested in a water flume.

“This experience stood out for me because it let us apply concepts using CAD software also used in industry,” Fieldsend says. “Each team member brought unique ideas based on their own background.”

For Martinez, a mechanical engineering and Spanish double major, it was a turning point.

“Submarines aren’t something I thought about often before, but this opened my eyes to how important and exciting this type of technology can be,” she says. “And it helped me clarify where I might want to take my engineering career.”

At the Australian Maritime College, students visited a cavitation research lab and witnessed advanced wave simulation in testing tanks used to study ship behavior in various ocean conditions.

At Flinders University, scholars met with members of the Maritime Engineering and Robotics team, which has been working on autonomous marine vehicles for almost 15 years. The students observed their Wave Adapter Modular Vehicle (WAM-V)—an unmanned surface craft being prepared for the maritime RobotX Challenge. The competition simulates real-world scenarios like underwater identification and obstacle navigation. They also toured the university’s robotics and remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV).

“At Flinders, we learned about the complexity of autonomous systems and how to build and design a submarine,” says civil engineering major Shepard, who returned from the trip inspired to launch the UConn Human Powered Submarine Club. “This trip was academically stimulating—and we also became close friends with the students there.”

Cultural Differences

Beyond the countless academic experiences, the scholars experienced Australia’s culture and landscape—encountering kangaroos, wallabies, and koalas at a wildlife park, swimming in Tasmania’s Cataract Gorge, and cheering on the Adelaide Strikers at a local cricket match.

“The rules and structure of the game were quite different from sports that we’re familiar with, making it a unique and fascinating experience,” Martinez says. “Additionally, we attended a tennis match, a sport we are more accustomed to, and witnessed the excitement from the lens of Australian locals while cheering for their home team’s player.”

Funding and the Future

AUKUS Scholar funding is provided by the Undersea Technology Innovation Consortium (UTIC), a joint effort between industry partners and academic institutions to promote the rapid development, prototyping, and commercialization of innovative technologies within the undersea and maritime sectors. Additional support came from a U.S. Department of State IDEAS grant, UConn and URI.

Although the program did not offer academic credit, NIUVT and OGA are currently developing a new 3-credit short-term course titled “AUKUS Down Under: Introduction to Maritime and Undersea Technology and Design” for winter break 2026. Additionally, students can study abroad at the University of Adelaide for one or two semesters.

“It’s exciting to watch students realize, ‘I could actually study Navy-related engineering topics in Australia. I could go now, or in the future I might even work there or collaborate with Australian partners here in the U.S.,’” Donegan says. “Some may even find themselves in careers that involve traveling between both countries. Our world is becoming smaller, and suddenly, it all feels possible.”

That’s exactly what Martinez is considering.

“My post-graduation plans aren’t set in stone, but now there’s more of a clear trajectory,” she says. “One thing I know for sure is that I’d love to work in engineering in Australia one day.”

UConn mentors Donegan; Christenson; Jiong Tang, professor in the School of Mechanical, Aerospace, and Manufacturing Engineering; and Kristin Morgan, assistant professor of biomedical engineering, along with URI mentors Jim Miller, Stephen Licht, Michalah Miller, and Frances Truong, supported the scholars throughout their experience.

Latest UConn Today

- Archiving for Justice, Truth, and Memory: Unpacking the Baggage of What Went BeforeReflections on the importance of the newest addition to UConn’s ICTY Digital Archives, the Srebrenica Genocide Archives Collection.

- Multiple Sclerosis Patient Sees Bright FutureFrom unheard to understood

- American Academy of Nursing Announces its 2025 Fellows Including Three UConn School of Nursing FacultyMallory Perry-Eaddy, Ph.D., RN, CCRN, Tiffany Kelley, Ph.D., MBA, RN, NI-BC, FNAP, and Gee Su Yang, Ph.D., RN, will be inducted as Fellows into the American Academy of Nursing.

- Finding New Strategies for Treating a Catastrophic DiseaseFoot and Mouth Disease was eradicated in the US in 1929, and researchers are working to make sure it stays that way

- Geothermal Brine May Hold a Key to Stored Energy ChallengesMaking domestic lithium recovery economically and environmentally viable is a critical goal for meeting the nation’s increasing appetite for energy storage and sustainability

- UConn Medical Students Learning to Strike Out Organ Donation InequitiesNew England Donor Services Launches New Medical Student Summer Immersion Program to Advance the Future of Organ Donation and Transplant Equity.