Sweet Disguise: Body Hides RNA With Sugar

To our immune system, naked RNA is a sign of a viral or bacterial invasion and must be attacked. But our own cells also have RNA. To ward off trouble, our cells clothe their RNA in sugars, Vijay Rathinam and colleagues in the UConn School of Medicine and Ryan Flynn at Boston Children’s Hospital report on Aug. 6 in Nature.

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a family of large biological molecules fundamental to all forms of life, including viruses, bacteria, and animals. Viruses as diverse as measles, influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and rabies all have RNA, which is why the immune system starts attacking when it sees RNA in the bloodstream or in other inappropriate locations. But our own cells have RNA as well, sometimes displaying it on their surface, plain for roaming immune cells to see – and yet the immune system ignores it.

“Recognizing RNA as a sign of infection is problematic, as every single cell in our body has RNA,” says UConn School of Medicine immunologist Vijay Rathinam.

The question is how does our immune system distinguish our own RNA from that of dangerous invaders?

Previous research led by Boston Children’s Hospital and Stanford University researchers Ryan Flynn and Carolyn Bertozzi had noticed that our bodies add sugars onto RNA. These sugarcoated RNAs (also known as glycosylated RNAs, or glycoRNAs) are displayed on the cell surface and don’t seem to provoke the immune system.

Rathinam and his colleagues wondered whether the sugar was somehow shielding the glycoRNAs from the immune system. This could be a strategy the body uses to prevent our own RNA from provoking inflammation.

When Vincent Graziano, a Ph.D. student in Rathinam’s lab and lead author on the paper, took glycoRNA from human cell cultures and blood, cut off the sugars, and reintroduced it into cells, the immune cells attacked it. The immune cells had ignored the same RNA when it was sugarcoated.

“The sugarcoating hides our own RNA from the immune system,” Rathinam says.

It is particularly significant to our body because cells are often covered by glycoRNAs. When cells die and are cleaned up by the immune system, the sugarcoating of RNA prevents dead cells from unnecessarily stimulating inflammation.

The findings could help when thinking about autoimmune diseases. Certain autoimmune diseases, such as lupus, are associated with specific RNA and dead cells setting off the immune system. Now that scientists understand the role of RNA glycosylation in deflecting immune system attention, they can check on whether that strategy is somehow going awry, and, if so, how it might be fixed.

This study was done in collaboration with the laboratories of Ryan Flynn, Thomas Carell, Franck Barrat, Beiyan Zhou, Sivapriya Kailasan Vanaja, Michael Wilson, and Penghua Wang and was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Latest UConn Today

- Anne C. Dailey Named Board of Trustees Distinguished ProfessorDailey is one of three UConn professors to receive the prestigious honor this year.

- UConn School of Nursing Students Spend a ‘Life-Changing’ Summer AbroadStudents participate in a 6-week Experiential Global Learning Program in Rwanda

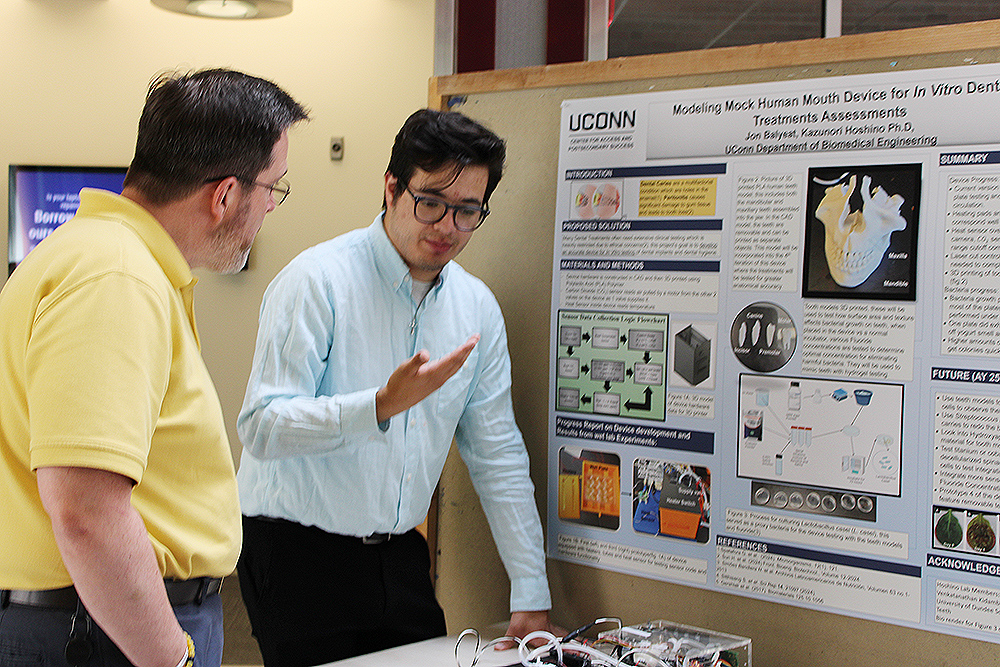

- CAPS Research Scholar Develops ‘Mock Mouth’ for Dental ResearchThe 3D-printed device, created by biomedical engineering major Jon Balyeat ’27, can show how microbial growth responds to oral treatments and implants without clinical trials

- Recommendations for Improving Black Women HIV Care and Racial EquityUConn Health Disparities Institute share their insights about the national Black Women First Initiative and the path forward to improved care for Black women with HIV.

- Life with Lori June: Professor Turns Kitchen into Classroom to Show Us How She Does It'I guess my life is a lot about food. It’s my creative outlet. Food is the way that I love people. Life with Lori June is just a new extension of that'

- CAPS Summer Program Concludes With Poster ExhibitionDuring the CAPS Research Summer program, students dedicate efforts to their research projects and leverage skills to be applicants for research-focused graduate degrees